By Julia Schiavoni

Throughout the course of history, cultural practices have ebbed and flowed alongside regional societal norms. In more recent decades, the promotion of women’s rights has increasingly become a global issue, however, not all countries have prioritized it to the same extent, specifically in regard to FGM.

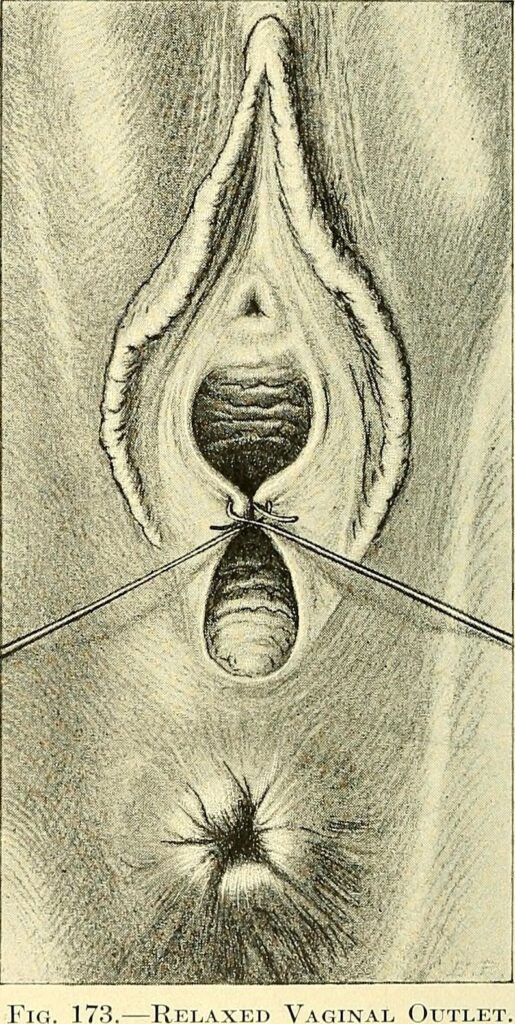

FGM, which stands for Female Genital Mutilation/Circumcision, is the general term used to describe any harmful and unnecessary cutting to a female’s exterior reproductive organs. As described by the President of the International Islamic Centre for Population Studies and Research, G.I. Serour,

“FGM/C is an extreme example of discrimination based on sex as a way to control women’s sexuality. FGM/C denies girls and women full enjoyment of their personal, physical, and psychological integrity, rights, and liberties. FGM/C is an irreparable, irreversible abuse of the female child. It violates girls’ “right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to protection,” contrary to the ethical principles of beneficence, justice, and non-maleficence.” 4

G. I. Serour, Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

For more information on what exactly constitutes FGM as well as the consequences of it, visit this WHO resource: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation#:~:text=Key%20facts,benefits%20for%20girls%20and%20women.

The question of, ‘What is FMG?” is much simpler than, ‘Why FGM’. However, as it is a practice that has been baked into cultures for centuries, the logical rationale for why it hasn’t been stopped despite almost universal condemnation is that some traditions are simply hard to shake… unfortunately though, this logic falters in countries such as Egypt because, instead of dying out, it has instead infiltrated the realm of higher education in the form medicalization.

Now, it should be noted that FGM is not at all isolated to Egypt nor Islam, and is in fact prevalent in various continents and religious cultures, however, I chose to concentrate this research on Egypt not only because it has high rates of FGM but also because the presiding religion is rather uniform. These two factors made the analysis more manageable because they narrow my work to a more finite set of cultural beliefs. To further iterate, FGM is not isolated to any one religion but they have rather co-evolved.

What Are The Origins of FGM?

To understand why FGM has been able to bleed into the sphere of medicine, we must first we must look to the origins of FGM itself. According to G.I. Serour’s paper, “Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting”, the origins of FGM are not entirely clear to academia, however, there is evidence to suggest that it predates Islam entirely and is connected to ancient regional traditions. Serous articulates that, even in 500 B.C., FGM was reported in Egyptian, Ethiopian, and Phoenician cultures, indicating that it is inherently much older than any Abrahamic tradition4. This history disproves the dangerous stereotype that FGM originated out of Islam. Another shocking discovery was that some historians even have reason to believe that the original purpose of FGM was not solely to control female bodies, but rather to officially discern ones gender. This idea is sustained by scholar, Otto Meinardus who argues that ancient Pharaonic cultures saw all people as reflections of the gods and therefore naturally ‘bi-sexual’… meaning, in this context, that people contained both feminine and masculine features. And that the only way to delineate gender was to remove from men, their ‘feminine’ aspects (foreskin) and from women, their ‘masculine’ aspects, aka, the clitoris3.

How is FGM Positioned in Current Egyptian Culture?

Regional Egyptian culture and social norms have drastically changed since 500 BC, however, FGM has been maintained… but why? Although they might be veiled in false Islamic explanations, the current justifications align much more with patriarchal methods intended to regulate the lives of women. In terms of culture, FGM is thought to promote virginity and prevent ‘sexual frustration’ by deadening sexual pleasure4. Given that there is no equivalent reduction of sensation for males in this society, it is evident that FGM is being weaponized to control women and their actions in order to bolster the relative power of men. In terms of religion, people (both men and women) who support FGM in Egypt often claim that FGM is important for their Islamic beliefs, but rarely are they able to cite any Qu’uranic justifications4. The only implicit connection to FGM that can be made to the Qu’uran is the use of the word ‘Tehara’, which means hygiene and cleanliness, however, its definition has been conflated to also mean ‘purification via mutilation’, which is a bit of a stretch4. Despite being condemned by religious leaders and state legislators, these ideas have become the foundation of the current Egyptian norms and are exceedingly difficult to deviate from.

Why has FGM become Medicalized?

To bring this issue to scale, in 2015, the Egyptian Health Issue Survey reported that of all women between the ages of 15 and 49, 87% of them had reported undergoing FGM1.

EGyptian Health Issues Survey – 2015

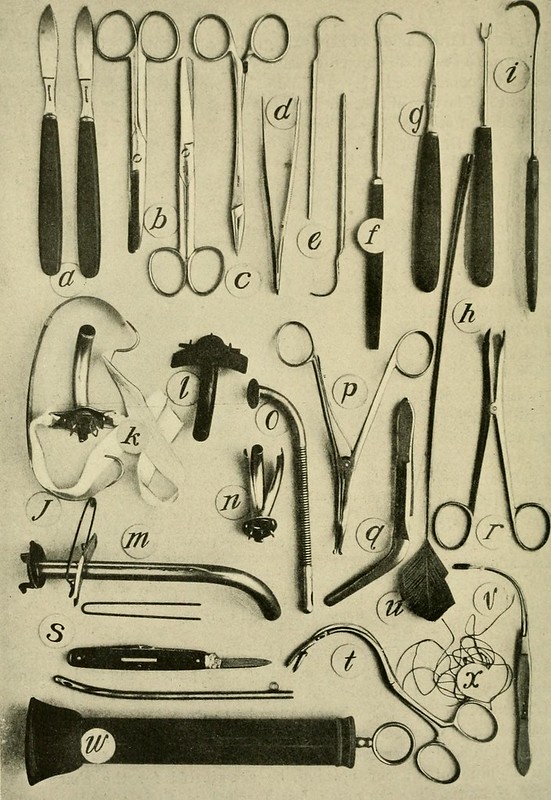

The actual cutting involved with FGM in Egypt has typically been done by community members such as barbers or traditional healers, however, due to the recent vocalizations about health risks, this practice has been shifting more into the hands of medical professionals. Egypt currently has the second highest rate of FGM medicalization which has been recorded at around 38% 2. The largest catalyst for this transition has ironically been linked to FGM awareness campaigns and the increased dispersion of information regarding the legitimate dangers associated with traditional FMG 2. Medicalizing FGM was initially thought to function as a harm reduction strategy which, was even at one point encouraged by the Egyptian government as a ‘safer’ alternative, however, the global consensus now condemns this approach because, even in more sanitary conditions, medicalized FGM still perpetuates unnecessary harm2.

“Whilst medicalized FGM/C might minimize – but not avoid – some of the long-term physical consequences of FGM/C, the fact remains that there are no perceived health benefits of the practice itself. It is therefore considered to be against good medical practice and a violation of the medical code of ethics, as even “do less harm” is contradictory to the Oath of Hippocrates ‘do no harm’.” 2

Els Leye et al., Debating Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Learning From (Policy) Experiences Across Countries

Even if preformed in an operating room by a legal physician, nurse, or plastic surgeon, FGM inherently violates any type of medical code of ethics principle relating to “Do No Harm”2. And given the current scale of this issue, I am left to wonder…how has modern medicine become so hypocritical? Physicians and other medical professionals have to dedicate large fractions of their lives to improving the health of others, and for them to be so blind to the harm that this sustains is astonishing; especially since these are the individuals who are supposed to be the wise products of higher education.

One of the unfortunate truths that I have discovered is that many medical professionals do it for the supplementary income. Although medicalization of FGM is technically banned in public hospitals in Egypt, there is still an abundance of room for it to be practiced elsewhere with little to no legal retributions4. On top of that, procedures of this nature are even more difficult to regulate when there is financial incentive supporting them. The Egyptian medical system is also not the most lucrative, which sadly makes FGM that much more incentivising2.

Apart form financial gain, many medical professionals in the region did not grow up isolated from Egyptian culture, hence why many often share the belief that FGM is a necessary cultural norm. As quoted from the journal article titled, Debating Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Learning From (Policy) Experiences Across Countries,

“Many health professionals are not aware of the long-term health implications of FGM/C and the fact that it is a violation of human rights and a breach of medical ethics, despite many regional and global protocols cited above condemning it. Moreover, health professionals often share the social norms of FGM/C being an important cultural tradition.”2

Els Leye et al., Debating Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Learning From (Policy) Experiences Across Countries

Why is Medicalization Problematic?

Medicalized FGM is known to cause PTSD and often-times, irreversible mutilation to women’s bodies2, and one of my greatest concerns at present, is for the rumors of medicalization’s ‘safety’ to encourage FGM prevalence as a whole. Medicalization of FGM is already on the rise in Egypt, and although global trends of FGM are beginning to decline I fear that medicalizing FGM may counteract that progress2. More effort needs to put into medical reproductive training to dissuade professionals from normalizing this practice in the region, but FGM at its root, will never be fully demolished until there is no perceived need for it in society. Religious leaders and other prominent community members who have the ability to influence the attitudes of the public need to be vocal about the lack of FGM justification within the Qu’uran. Dissociating FGM from the teachings of Islam is the first step towards dissociating it from the presiding culture as a whole, but without that, no change will be had. To reiterate, Serour argues that scholars have already proven that FGM traditions have no legitimate ties to the Prophet Mohamed… the challenge is now, however, to convey these truths to swarths of people who have been raised to think otherwise.

——————————————————————————————————-

References:

- El-Zanaty and Associated. Rep. EGYPT HEALTH ISSUES SURVEY 2015. Cairo, Egypt: DHS Program, 2015.

- Leye, Els, Nina Van Eekert, Simukai Shamu, Tammary Esho, and Hazel Barrett. “Debating Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/c): Learning from (Policy) Experiences across Countries.” Reproductive Health 16, no. 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0817-3.

- Meinardus, Otto. “Mythological, Historical, and Sociological Aspects of the Practice of Female Circumcision Among the Egyptians .” Acta Ethnographica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 1967, 387–97.

- Serour, G.I. “Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting.” African Journal of Urology 19, no. 3 (2013): 145–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afju.2013.02.004.

Julia, I learned so much from this project. I had little background knowledge of female genital mutilation, specifically in Egypt, and I feel the way you laid everything out in your presentation was incredibly insightful and easy to understand. I appreciated how you included basics like the origin of female genital mutilation because it gave me a more whole perspective on the complex issue you researched. I completely agree with you that more effort needs to be put into medical reproductive training to dissuade professionals from normalizing this practice in the region. It’s sad but probably true that it will be intensely difficult, even impossible, to eradicate the practice completely.

Well done! We wrote both wrote about genital mutilation for our projects.

You wrote “Given that there is no equivalent reduction of sensation for males in this society”.

Reduction of sensation can’t be quantitatively measured or compared between the sexes, but there’s a definite reduction of sensation for males in the same society, caused by male genital mutilation, which is common in Egypt and in every other country in which female genital mutilation is common. The most common type of female genital mutilation in Egypt is type 1a (often called circumcision), which consists of the removal of the prepuce, the exact same tissue that is removed during the predominant form of male genital mutilation in Egypt. Excision of the prepuce causes reduced sexual pleasure and sensation regardless of whether the prepuce was covering a clitoris or a glans penis. To read more about the reduction, see my paper or one of many studies on the reduction of sensation after removal of the prepuce. The parts that are cut off are homologous and equivalent, so the reduction in sensation is equivalent as well, though that cannot be objectively measured. If a man had his left arm cut off, and a woman did too, though it’d be impossible to measure the reduction of sensation caused by the loss of their respective arms, it’d be most logical to assume equivalence because of the parts’ equivalence.

You wrote:

“In terms of religion, people (both men and women) who support FGM in Egypt often claim that FGM is important for their Islamic beliefs, but rarely are they able to cite any Qu’uranic [sic] justifications … Religious leaders and other prominent community members who have the ability to influence the attitudes of the public need to be vocal about the lack of FGM justification within the Qu’uran [sic]. Dissociating FGM from the teachings of Islam is the first step towards dissociating it from the presiding culture as a whole, but without that, no change will be had. To reiterate, Serour argues that scholars have already proven that FGM traditions have no legitimate ties to the Prophet Mohamed [sic]…”

Though it’s indeed true that there’s no mention of female or male circumcision in the Qur’an, as I wrote in my paper, there are numerous aḥādīth supporting female and male circumcision, and some (but not all) schools of Islam consider the practices to be required or recommended. Islam isn’t just derived from the Qur’an, but also from the sunnah and aḥādīth, and thus many muslimūn and muslimāt consider genital mutilation to be part of their faith, and practice it as such. (See my paper for the specific aḥādīth.)

In my paper, I cited some papers calling out American opposition to female circumcision as hypocritical, cognitively dissonant, culturally imperialistic, and colonialist. I question whether it’s our right at all to tell others how to practice their own respective religions and cultures, even though many traditional religious and cultural practices include cutting off parts of children’s genitals. Though I fundamentally disagree with the practice of mutilating children’s genitals and believe it to be morally wrong, it’s an important part of many people’s cultural and/or religious traditions, and I don’t think it’s my place to try to stop it, nor do I think my condemnation will do anything. I also think more criminalization of child genital mutilation would just make it more dangerous for children, as people will simply continue to do it, just not in a doctor’s office or hospital.

I enjoyed reading your project, it was well written and interesting, and your choice to focus on one form of genital mutilation within one specific country allowed to you to write in a lot of detail.

I found it really fascinating how you examine the ethics of FGM, especially regarding harm reduction efforts and the monetization of the practice. The way that medicalizing FGM ended up contributing to its prevalence is such a good example of how cultural practices evolve to stay relevant, given the demands and values of modern society. I also like how you consider factors beyond the practice itself, like monetary gain for doctors, that contribute to the medicalization and continuation of FGM. I think it can be really easy to isolate the discussion of practices to ethics, but these practices don’t exist in a vacuum, so I appreciate how you considered the other contributing factors.

This project was so informative! I honestly feel quite oblivious for not being aware of this issue prior to taking this class and listening to the projects regarding this specific topic. It is super intriguing to see and inspect the line between something being culturally important and something being a violation of rights and just so extremely invasive. The origins of FGM being “unconfirmed” was also interesting and the one rationale for FGM being used to discern gender was something that I didn’t expect at all. Overall, I really appreciate how comprehensive this project is – I learned so much.

I enjoyed your project, and I like how you narrowed down your topic so that you were able to go more in depth about a specific thing without the project being overwhelmingly long. It is concerning how this is being done, and while the medicalization of it may make the procedure safer, there are still so many issues with FGM, particularly the permanent effects it has on women who undergo the procedure. I like how you mentioned the issues medical professionals face when addressing this situation, especially the “do no harm” aspect of things.

Your presentation was so interesting and clearly really well researched! I’m taking a class on Female Genital Mutilation right now but my professor is not amazing so I really enjoyed your presentation as I learned a lot that I didn’t in a semester long course. For example, I was really surprised by the quote at that says that health professionals view FGM as being an important cultural tradition as I assumed that they would be the first to criticize it. I also like how you point out that by medicalizing FGM people may at first glance think this is positive cause it may make the procedure slightly safer, it still violates the medical cole of ethics principle relating to “Do No Harm.” Great job!

Your presentation was so interesting and clearly really well researched! I’m taking a class on Female Genital Mutilation right now but my professor is not amazing so I really enjoyed your presentation as I learned a lot that I didn’t in a semester long course. For example, I was really surprised by the quote at that says that health professionals view FGM as being an important cultural tradition as I assumed that they would be the first to criticize it. I also like how you point out that by medicalizing FGM people may at first glance think this is positive cause it may make the procedure slightly safer, it still violates the medical code of ethics principle relating to “Do No Harm.” Great job!

Your project was so interesting and informative. I had never learned anything about female genital mutilation, so your project was definitely eye opening. I feel like there are so many ways in which women’s bodies are controlled by societies and this brought a new area of attention to focus on to my base of knowledge. In particular, your research on how health professions regard FMG as an “important cultural tradition,” despite its negative health consequences and ignorance of medical ethics was so interesting.

I thought your project was really interesting and so well-researched! I really liked that you made a point of saying that you only picked Egypt because it made the research a little more manageable, and no other reason. I also really liked how you explored the origins of FGM, and how you pointed out that no one really knows the exact origin, but it predated any of the world religions. Overall I thought you had a really great project!

Julia, this was a great project! I thought your topic was really interesting. I liked that you focused on female genital mutilation and specifically its practices in Egypt. I knew a bit about the subject but I became a lot more educated after reading your project and listening to your presentation. It was really sad to hear that female genital mutilation is being used as a tool to control women in Egypt. It was crazy to hear that mothers sometimes will make their daughters get FMG because it will make them more desirable for marriage. It was sad to hear that although the practice is technically illegal now, that some doctors still perform it under the table. Super informative and great project overall!

Julia, I really enjoyed listening to your project! I had not really heard much of this topic before. When you introduced your project, I was a bit surprised, I never knew that was a problem for women. It was very informative and detailed. Although your actual presentation was cut a bit short, I made sure to go back and read up on your work! I also was surprised when you mentioned how female genital mutilation outdates any world religion, that’s a bit crazy to think about! Great job and amazing work!

Julia, your project was super informative! I really appreciated your choice to focus deeply on just one country’s history of FGM, as it allowed you to really dive into the topic instead of just surveying it. I was very fascinated by how many medical professionals in Egypt perform FGM for extra money, as it reminded me of how the American healthcare system encourages circumcisions due to their cost. This reveals how money tends to preside over ethics across countries and cultures.

Julia, this was so well done, thank you for researching such an important topic. I wish young women were not the victim in these situations. I thought it was interesting how there is no clear religious basis for this procedure in the Qu’ran, but this interpretation of purity is still being enforced. I also find it sad and disturbing that this medical procedure is irreversible and completely violates the the medical code of ethics. Thank you for taking the time research this extensively, I definitely want to learn more about this topic. I was wondering if you found anything about any clear opposition to FGM in Egypt; is there any resistance?

I was really looking forward to hearing about this project as I had previously before only focused on FGM in some Western African countries. I like how you critique some women’s movements as to not focusing more attention on these issues as they do typically go disregarded. I found it interesting how people were concerned with its safety so they urged FGM in Egypt to become medicalised, but that is what people began to find concerning since the process is problematic in all aspects. Hopefully, this issue becomes more targeted and the right people become sanctioned for it. Great work!